Magnus, Unyielding:

“You come at the king. You best not miss.”[0]

No Endless Draws, No Endgame Deadlocks

The name “Armageddon” refers to the final battle that brings the Apocalypse to a close: the image of an ultimate reckoning. In chess, this format is reserved for the most extreme of tiebreaks. A draw is not an option. White is granted more time but must win to prevail. If not, they lose. It is the last resort, the razor’s edge: all or nothing.

In addition to the main section, the tournament featured two additional events: a women’s tournament with six participants, following the same double round-robin format, with identical prizes and sharing the playing hall with the open event; and an open tournament, with a broader pool of players and a different structure. A competition with many sections, but a single essence: chess at its finest.

Norway Chess, Round 6 (2025): A Wavering Crown in Stavanger

Magnus Carlsen was defeated by Dommaraju Gukesh (internationally known as Gukesh D), the current world chess champion, in the sixth round of Norway Chess 2025. And this defeat, although surprising in sporting terms, holds a far deeper symbolic meaning.

The spark for this article was the superficiality with which both the game and its immediate aftermath were discussed in many circles. Magnus’s final mistake was exaggerated, overshadowing Gukesh’s historic victory, and the moment when Magnus, realising he had lost, struck the table violently before resigning was trivialised. Both responses warrant criticism. On one hand, coverage that reduces chess to a catalogue of blunders undermines a deeper understanding of the game and belittles the achievement of the young champion. On the other, for someone of Magnus’s stature, both as a player and a public figure, to react in such a way signals a problem that goes beyond personal frustration: it reflects a broader erosion of decorum, of certain unwritten codes of composure that are fading not only in sport, but across many spheres. And yet, none of this seems to diminish the near-mystical fervour with which millions follow him: an emotional attachment that goes beyond the board, and perhaps has no parallel in the history of modern chess.

It is striking, by contrast, to recall that when Bobby Fischer protested against the noise of cameras, the quality of lighting, or the “lobbying” among Soviet players, the pre-arranged draws that left him at a disadvantage, he was dismissed as capricious, paranoid, or eccentric. And yet, it is thanks to his intransigence that elite chess today is played under exemplary technical conditions, as Garry Kasparov has acknowledged on more than one occasion. The difference lies not only in the demands made by players, but in the kind of indulgence they are afforded. What was once judged as arrogance in Fischer now seems forgiven in Carlsen, as if part of an untouchable aura.

Kings Without Crowns, and Boards Without Scripts

Carlsen had already defeated Gukesh in the opening round, and was looking to do so again to reaffirm his status as the “legitimate king”, despite having voluntarily relinquished the title in July 2022. After that first victory, he posted a phrase on X (formerly Twitter) that inspired the title of this article: “You come at the king. You best not miss.” A provocative statement, considering that he had not lost the crown out of weakness but from lack of interest: classical chess, with its exhausting computer-based opening preparation, had become increasingly alien to his sense of artistry. Magnus prefers formats that free the imagination from the very first move, such as rapid chess and Chess960, now promoted under the name freestyle, where opening scripts vanish. For him, creativity should not have to wait twenty moves before showing itself. Still, he likes Norway Chess. It is accelerated classical: time pressure in the late middlegame, and Armageddon games for tiebreaks. That’s why he keeps playing.

Witnessing in person this clash between what many regard as the finest player of the 21st century so far, and the youngest world champion in history, in a hall where the tension is felt in the silence and every gaze is fixed on the monitors, is a rare privilege. And being able to do so for 200 Norwegian kroner (roughly 20 dollars for adults, or 100 kroner for those under 18), can hardly be considered expensive. Sometimes, a good memory is worth more than a thousand forgettable moments.

Gukesh, however, went further. His victory was no accident, but the culmination of a lucid defence against a rival who, at times, already fancied himself the winner. And here the original focus is restored: the game itself. Gukesh has yet to study the classics with the devotion Carlsen has shown, but his calculation is sharp, his resolve unshakable, and his mental strength is supported by one of the most respected sports psychologists on the circuit. The table shook, yes. But it was not the only thing that trembled: so too did the symbolic balance of contemporary chess.

The Threat Carried Out: Merit, Error, and Outcome

What happened that day was no anomaly: it was a demonstration that, even when facing a king, mere threats are not enough. One must carry them out. There are critical moments when the threat is much stronger than the execution. [2]

Magnus’s recent defeat against Gukesh represents far more than a sporting upset. It is a scene laden with meaning: a modern fable that invites us to reconsider the nature of victory, competitive justice, the psychology of error, and the complex relationship between merit and outcome.

Carlsen had steered the game clearly up to move 42. His dominance was such that victory seemed a foregone conclusion. But chess, like life, offers no guarantees. Gukesh, without flamboyant gestures, showed lucid resistance. Most likely lost, he kept playing. And when Carlsen made minor errors, he turned the tables.

The widespread belief that the player who played better for most of the game “deserves” to win is as seductive as it is false. In chess, partial merit does not automatically translate into a final result.

From Advantage to Abyss: The Ruthless Logic of the Outcome

If we recall that “errors are there to be made” (Die Fehler sind dazu da, um gemacht zu werden), as Savielly Tartakower put it in 1924, the trick lies in knowing, under pressure and tension, how to capitalise on the opponent’s mistakes while avoiding one’s own. Victory does not depend on having shone during a stretch of the game, but on not faltering at the decisive moment.

The player in the lead often falls into the trap of complacency: they believe the game will win itself. Meanwhile, the one who is behind is freed from pressure and plays with renewed clarity.

That is what happened in Stavanger. And not only in chess. Sport has seen many great promises undone by the outcome. In the 1950 FIFA World Cup, Brazil played the final as hosts in a newly inaugurated Maracanã stadium, in front of nearly 200,000 spectators. They only needed a draw. Uruguay, with nothing to lose, snatched glory away from them.

In 1954, Hungary were firm favourites. Led by Puskás, they had convincingly defeated every opponent, including Germany, scoring eight goals against them in the group stage. But in the final, when they seemed poised for the title, the Hungarian side let their lead slip and lost the match. In 1974, something different but equally painful befell the Netherlands. With Rinus Michels as manager and Johan Cruyff at his peak, they reached the final showcasing a bold and innovative brand of football. Yet once again, it was West Germany who triumphed.

In all these cases, the team that had dazzled ended up defeated. Because in sport, as in life, merit is not enough. You must deliver.

Back to the board: what engines now call a flagrant or catastrophic error only became obvious once the game had ended. Neither Carlsen nor Gukesh saw it at the time. Human chess is played in the fog, not with oracles. Victory belongs to the one who remains clear-headed until the end. Who played better? It’s a trick question. In truth, it doesn’t matter who played better for a portion of the game. This isn’t a style contest, but a duel where the decisive factor is neither prior dominance nor fleeting brilliance, but what ends up on the scoreboard. For the point to count, someone must tip their king in the end. And when everything hung by a thread, Gukesh found the right path. Carlsen dominated the middlegame. Gukesh shone when it mattered most. Chess does not reward isolated sparks, but sustained resilience. What happened at the end said it all: Carlsen slammed the table. Gukesh stood up in silence. No mockery, no excessive celebration. Only respect. Because even the king, if he wants to prevail, must play to the very end.

Of course, we know perfectly well that chess and football cannot be compared in their rules or nature. The sporting examples mentioned here are illustrative, not equivalent: they show that aesthetic, strategic or emotional dominance does not guarantee the result. In any competitive game, victory is not inherited; it must be earned. And no: drawing a comparison does not mean confusing the sports themselves.

Dissecting the Endgame

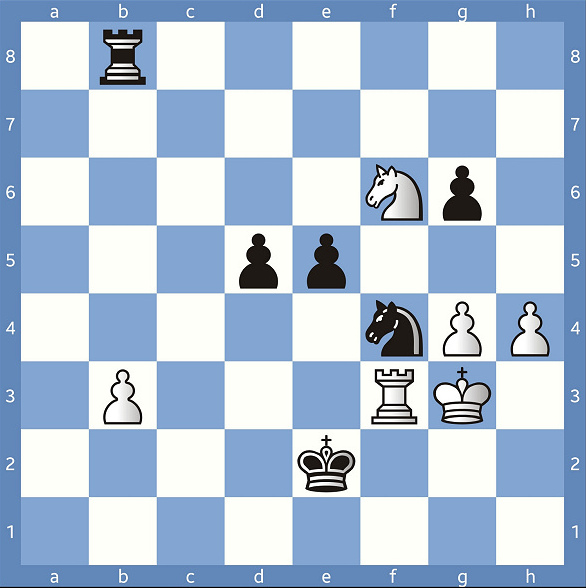

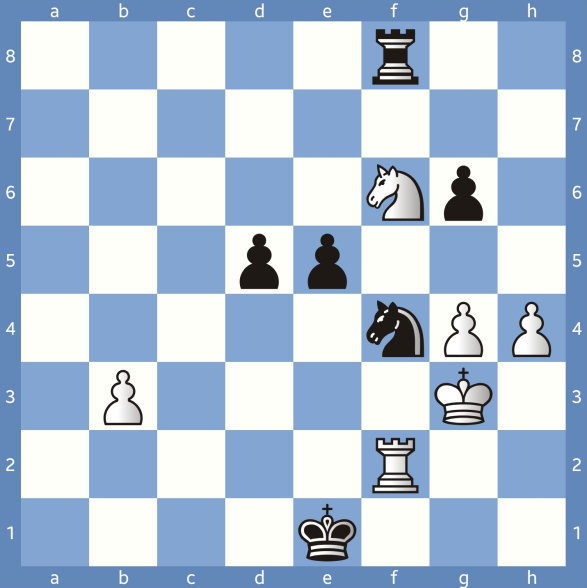

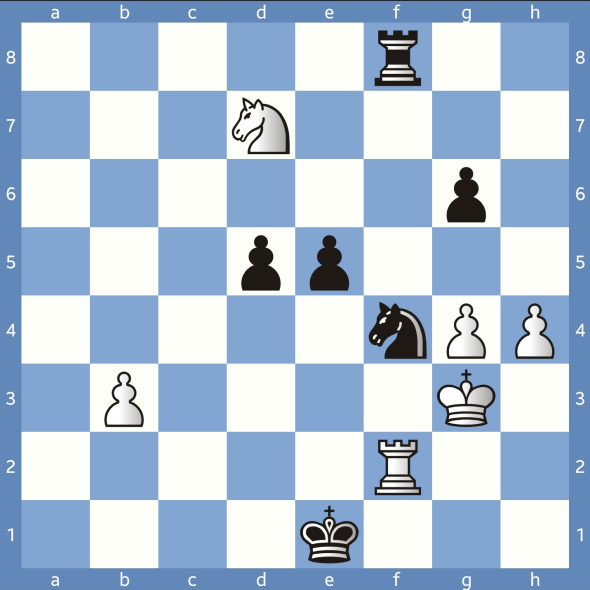

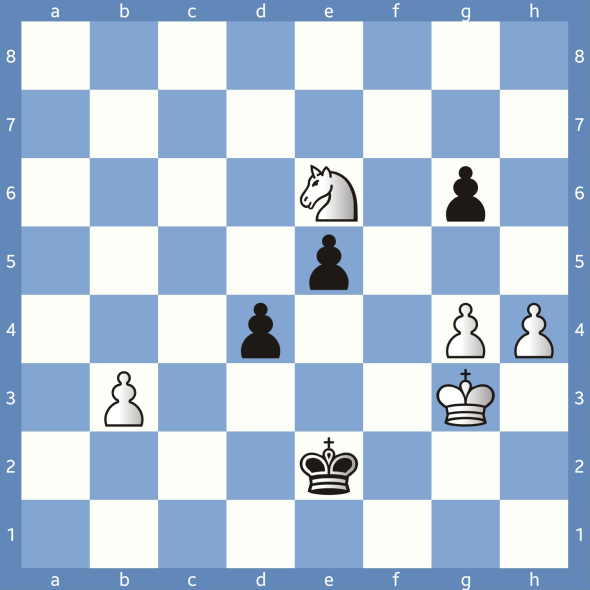

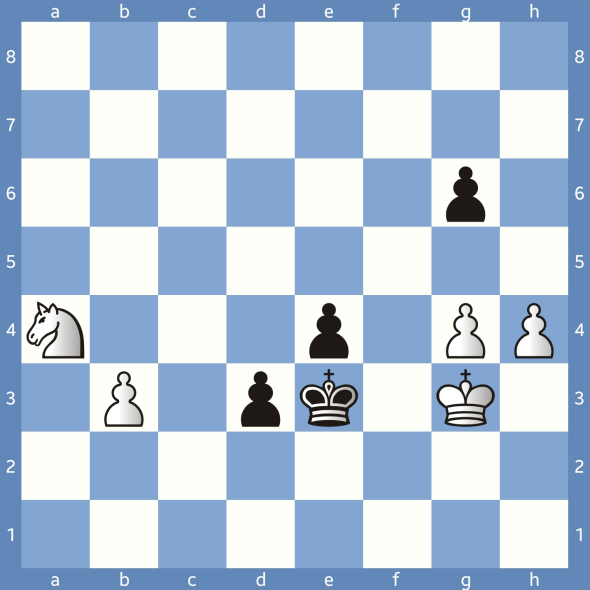

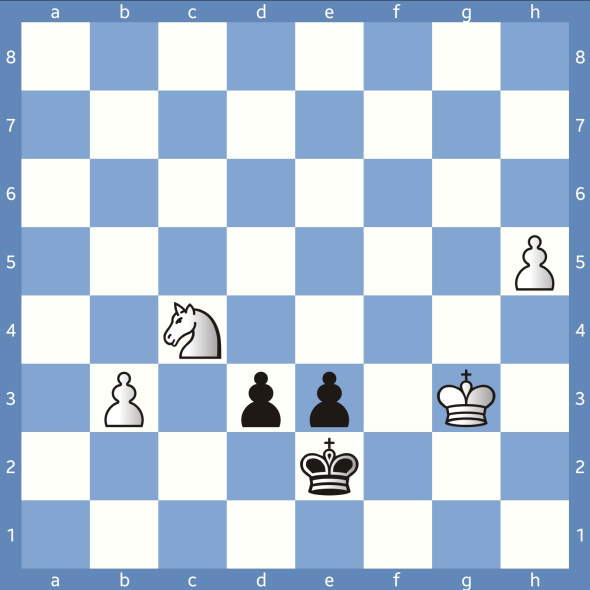

Let us now examine the final sequence in detail: the position after 50.Nf6 reveals how a seemingly balanced situation could suddenly collapse.

50...Rf8=

a) 50...Rd8 51.Rf2+! Kd3 52.Rf3+! (52.h5? gxh5 53.gxh5 Rf8 54.Ng4 Nxh5+ 55.Kg2 Rxf2+ 56.Kxf2 e4–+) 52...Kc2 (And if Black’s king, unwilling to abandon his pawns, chose 52...Kd4, the board would spring a surprise—subtle and elegant. White would then have access to a beautiful exchange sacrifice: 53.Rxf4+!! exf4+ 54.Kxf4 Rf8 55.Kg5!, reaching an equal position through the harmonious coordination of the white pieces. The rook sacrifice on f4, as aesthetic as it is functional, holds a classical lesson: in complex endings, it is not always material, but time and activity that tip the balance.) 53.h5!= Exploiting the fact that the black king has dropped a rank and can no longer support his pawns closely, White launches a precise kingside plan. The breakthrough is now fully justified: 53...gxh5 54.gxh5 Rd6 (54...Rf8 55.Ng4 Nxh5+ 56.Kf2) 55.Ng4. The position remains balanced, though it still allows for fine exploration.

b) 50...Rb5 51.Rf2+! Kd3 52.Rf3+ Kd2 53.Rf2+ Kc3 54.h5 gxh5 55.gxh5 Nxh5+ 56.Nxh5 e4 57.Kf4, with equality.

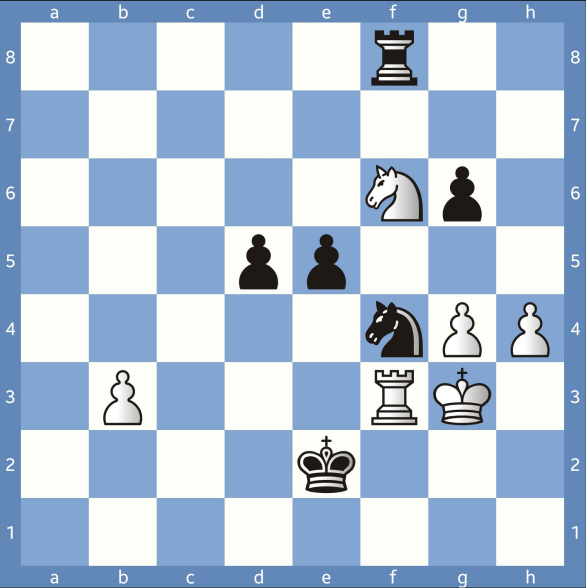

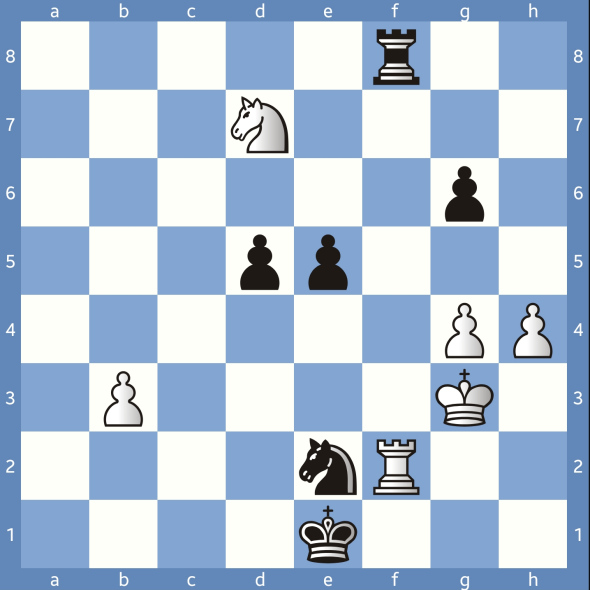

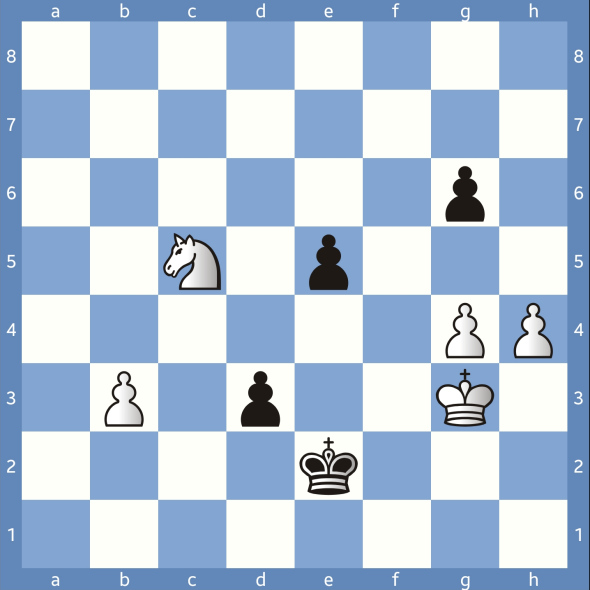

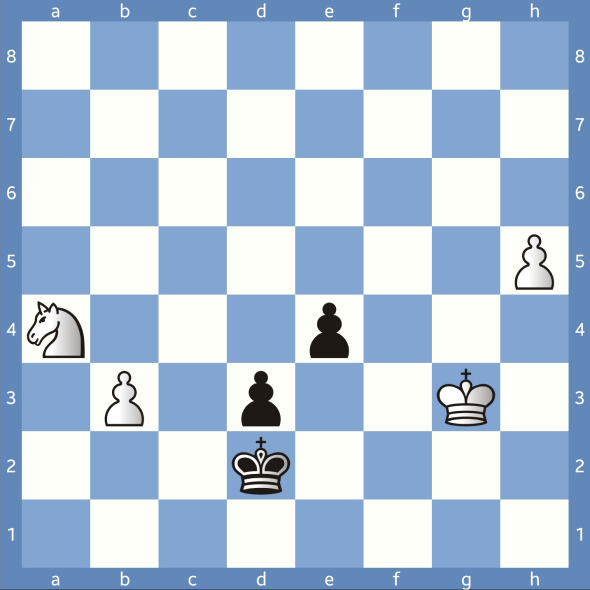

The Moment of Apparent Balance

51.Rf2+

This move is unique.

a) 51.Nd7?? Nf4+, and Black wins easily.

b) 51.g5? Nd3!, and White finds themselves in Zugzwang, from the German Zug (“move”) and Zwang (“compulsion” or “coercion”); a situation in which a player is disadvantaged simply because they must move.

51...Ke1

Magnus chooses to voluntarily step away from his central pawns. The resulting position carries a symbolic nuance: the black king now stands on the original square of the white monarch. A role reversal that, beyond the anecdotal, hints at a deeper psychological layer: the king taking initiative, but in doing so, straying far from his rear guard.

Instead of this move, let’s consider two genuine defensive attempts by Black:

a) 51...Ke3 52.Nxd5+!? (52.Nd7!? was also possible) 52...Ke4 53.Nxf4 exf4+ 54.Kg2, with equality maintained.

b) 51...Kd3 52.Nxd5!? (again, 52.Nd7!? offered a viable alternative) 52...Ne2+ 53.Kg2 Rb8, preserving dynamic balance.

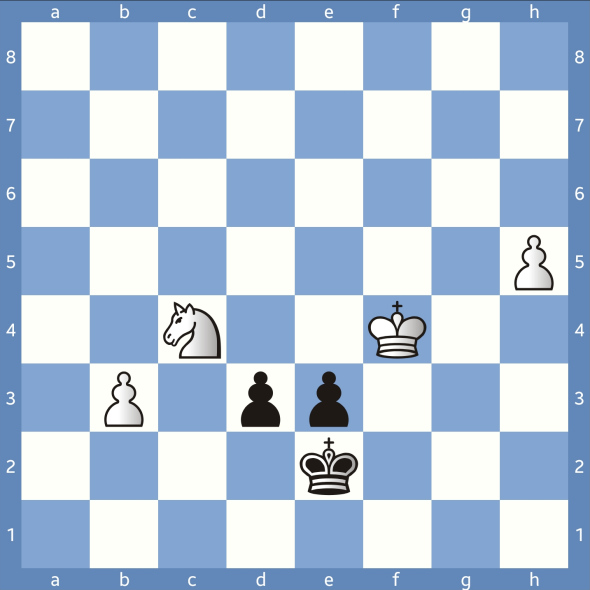

A Bold Decision Under Pressure

Up to that point, the game had followed the edge of an unstable balance. Black had ceded the initiative but still retained solid defensive resources. It was then that Gukesh, with only seconds on the clock, chose a path as risky as it was profound, likely trusting his instinct as a great player more than precise calculation.

52.Nd7!

At first glance, it seems like a naïve move: as if White were willingly sacrificing the exchange without visible compensation. But the underlying idea runs far deeper. It is not a tactical trap, but rather an invitation to enter an extremely delicate endgame, where a lone knight must face two connected central pawns, coordinated with their king. The weight of the decision thus falls upon precise calculation… and the ticking clock.

The clocks, cruel witnesses of the unfolding drama, show 21 seconds for Gukesh and just 12 for Magnus, when the latter, still caught in the strategic fog of the endgame, commits to:

52...Ne2+?

This is the move that shifts the balance and instantly electrifies the commentators, as though a last-minute goal had just been scored in extra time. The question mark does not signal a blunder in the classical sense, despite the outcry. It denotes a wrong path, forged in the crucible of a complex position under severe time pressure. At that critical moment, Magnus had only twelve seconds: he was practically forced to move, without having yet glimpsed a clear way out of the maze of variations and subtleties before him. It was not possible to unravel all the threads at play; initiative, coordination, structure. And in that uncertain edge, where calculation and intuition blur, a single decision is enough to alter the fate of the game.

Human Errors in the Age of Silicon

Clearly, the stir caused by Magnus’s slip owes more to a media overreaction, by commentators and spectators alike, than to a sober evaluation of what occurred. From the calm of our library, tea in hand, it is easy to pass judgment and conclude that his decision was indeed misguided.

In chess, I remain faithful to the classical notion of a blunder: an obvious, catastrophic mistake that drastically worsens the position immediately, such as losing a piece outright or allowing a forced mate. These mistakes are often evident even to club players, as they involve direct threats that could have been avoided with a minimum of attention. By contrast, a move that leads to defeat but is not obvious at first glance is not, to my mind, a “blunder”. It may be a positional misjudgement: unnecessarily weakening the pawn structure, closing lines at the wrong moment, or exchanging pieces unfavourably. These errors usually involve no immediate material loss and often go unnoticed by both players. Their strategic impact becomes clear only later, when the position has already tilted irreversibly.

I do not blame chess engines (also known as “analysis modules”) for this terminological confusion; their contribution to the study and refinement of the game is undeniable. I use them regularly to review my analyses and fine-tune the content of my notes or publications. I first became familiar with them during the days of Fritz 1, back in 1991, when it still fit on a floppy disk, and its strength was enough to humble most humans. I have no objection to their use. What does concern me, however, is how their presence—and more so, their overuse—has begun to distort the language of chess commentary.

I find it difficult to tolerate how casually a move played in Zeitnot by a world chess champion, after a tense and exhausting battle, is labelled a “blunder”, as though the engine’s infallible verdict could be transferred uncritically to the human domain. It is one thing when a professional overlooks a mate-in-one or hangs a piece, a mistake we call “colgada” in Río de la Plata Spanish. That’s a clear, undeniable blunder. But it is something entirely different when a human move stems from a complex evaluation, possibly flawed, in a position where each decision is made with seconds on the clock, adrenaline surging, and focus eroded by hours of tension. The engine issues its verdict in tenths of a second; the commentator repeats it with borrowed authority. But neither has lived that position from within the body that played it.

Gukesh himself, newly crowned world champion at the age of 19, later admitted that, in that very moment, he was not fully aware that the position had clearly tipped in his favour: “I sensed it, and I just focused on making the best move each time.” It was then that his command of tactical patterns and his calculating ability became strikingly evident, as though his mind were operating with the precision of a silicon processor.

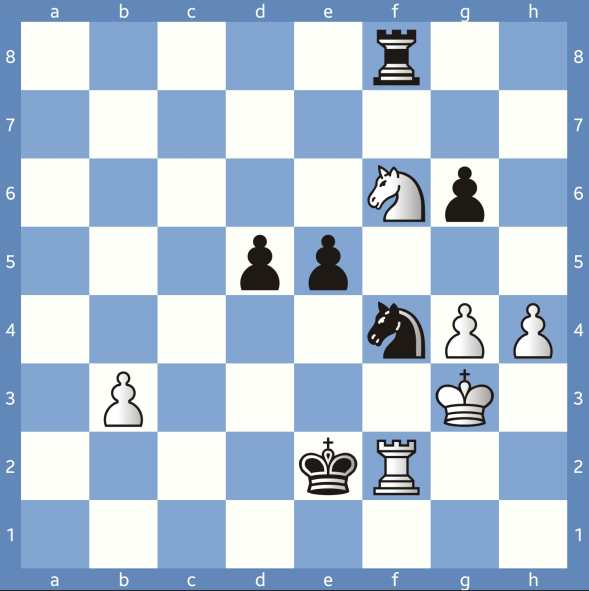

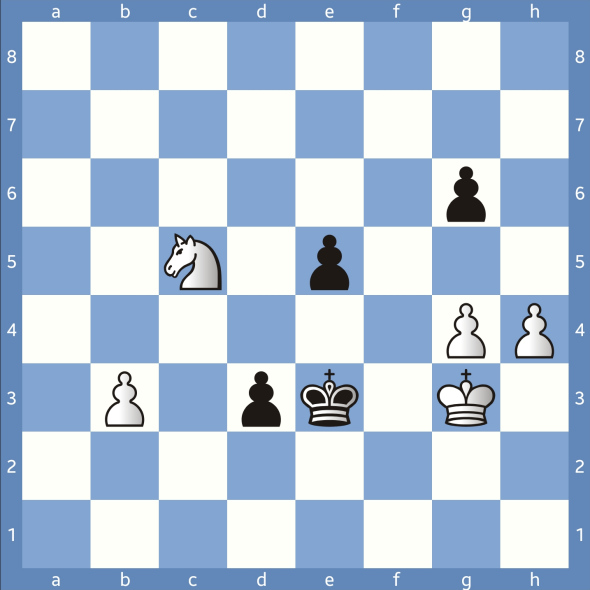

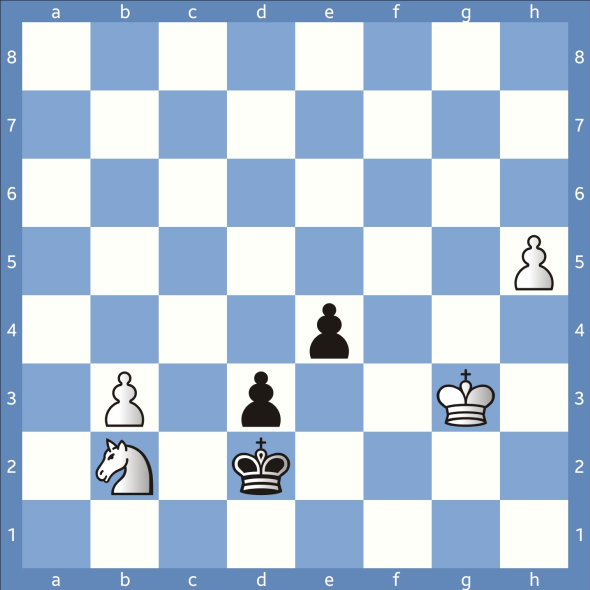

Magnus chose to insert a check, hastening the conclusion. Any reasonable rook move, such as 52...Re8, would have been enough to preserve the balance. For instance:

a) 53.Rxf4!? exf4+ 54.Kxf4 Re4+ 55.Kf3 (55.Kg5? d4–+) 55...Kd2 56.Nf6, and White is not worse.

b) 53.Nxe5!? Ne2+! 54.Rxe2+ Kxe2 55.Kf4 d4 56.Nc4! d3 57.h5 d2 (57...Rc8 58.hxg6=) 58.Nxd2 Kxd2 59.h6 Kc3 60.Kg5 Kxb3 61.Kxg6 (61.Kf6 Kc4 62.h7 Kd4 63.Kg7 g5 64.Kf6 Rh8 65.Kg7 Rb8 66.Kg6 Rh8=) 61...Kc4 62.Kf7 Rh8! — the only move, as the rook must keep watch over the 'h' pawn. (62...Ra8? 63.g5 Kd4 64.g6, and White would win. The g6 push is only possible when the rook is not on a8, as the a-pawn would fall) 63.g5 Kd4 64.Kg7 Ra8 65.h7 Ke5 66.g6 Kf5 — with equality.

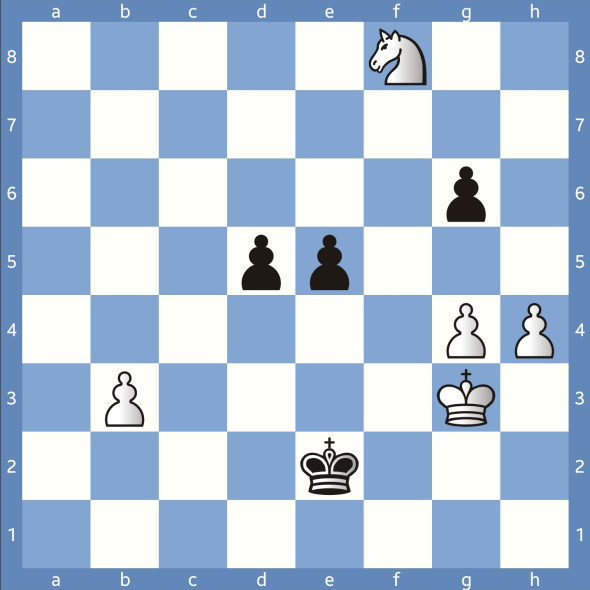

53.Rxe2+! Kxe2 54.Nxf8

When I saw this ending, a chapter from Mark Dvoretsky’s writings came to mind: “Once More About Montaigne’s Knight”, which I had studied years ago with Martín Marotta (1960–2020), a dear friend and refined correspondence player. In that chapter, Dvoretsky continues a reflection begun by Artur Yusupov in the previous one, “Knight Solo”, where he quotes Montaigne: “There are horses trained to attack an enemy who wields a sword.” What might have seemed an exotic image in the 16th century becomes, in the hands of great trainers, a symbol of the astonishing tactical and defensive capabilities of that enigmatic three-square rider. In the final phase of the Gukesh–Magnus game, it is precisely a knight on the eighth rank, solitary yet strategic, that upholds the heart of White’s position, holding back the pawn advance with precision. As if Montaigne’s spirit, and the echoes of those weekends studying with Martín, were still galloping across the board. Perhaps it is this ability to emerge from afar, full of unexpected resources, that unsettles even players of Magnus’s calibre, at least in critical time pressure.

Magnus now advances his infantry, but unless his opponent falters, the outcome is sealed.

54...d4

55.Ne6

The knight re-enters the fight, seeking the optimal path to arrive in time and prevent promotion.

55...d3 56.Nc5!

56.Ng5! was also possible. Via either path, the knight reaches e4: 56...d2 (56...Ke3 57.Nh3!+-) 57.Ne4!+-

56...Ke3

Black chooses 56...Ke3 to block the knight’s access to e4. After 56...d2? 57.Ne4! d1=N (or 57...d1=Q 58.Nc3+, followed by 59.Nxd1) 58.h5 would grant White a decisive advantage.

57.Na4

Naturally, this knight leap is White’s only available resource to stop the d-pawn from promoting.

57...e4

After this threatening advance of Magnus’s central pawns, promotion seems inevitable. Tarrasch once wrote: “Before the endgame, the gods have placed the middlegame.” I would dare to add, with reverent humour, that after the middlegame, the gods have placed the endgame. For there are endings that are not mere conclusions, but revelations.

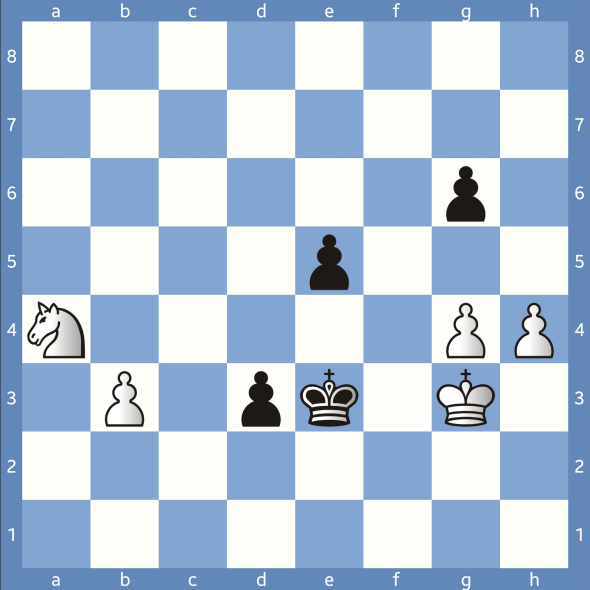

58.h5 gxh5 59.gxh5 Kd2

Magnus steps away from the e-file to clear a path for his king’s pawn. He may have expected 60.h6? e3 61.h7 e2 62.h8=Q e1=Q+. Yet in this ending, reminiscent of the work of Nikolai Grigoriev, Gukesh aspires to more than a simple draw.

60.Nb2!

A more exotic route would have been 60.Nb6! After 60...e3 and then 61.Nc4+ Ke2 62.Kf4, the same favourable conclusion would have been reached via a different but equally elegant path.

However, the route chosen by Gukesh is more natural. And I suspect that, in playing it, he already saw clearly that the game was his. He executed it with such vigour and momentum that he accidentally knocked over his own b-pawn; a telling sign of accumulated tension… and of the imminence of triumph.

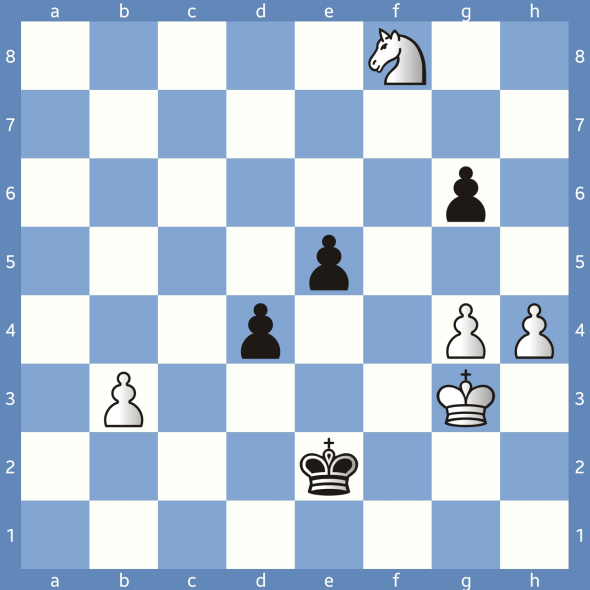

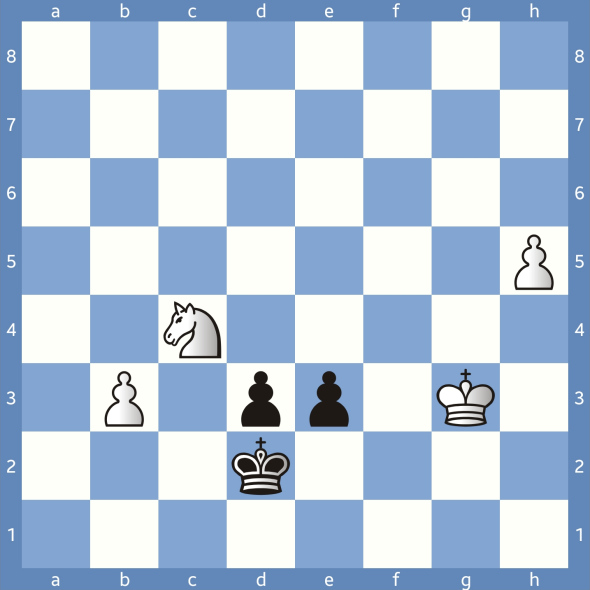

60...e3 61.Nc4+

Anyone unfamiliar with the context might think this is a composed study: a sequence of moves so precise it could hardly have arisen by chance, a geometry of pieces aligning like verses in a tactical poem.

This ending bears the unmistakable stamp of composition, where logic disguises itself as miracle and necessity takes on an air of aesthetic inevitability: that white knight from f8 ends up on c4 just in time to capture the king’s pawn and stop the opponent from queening. And yet, this wasn’t art born in the quiet of a study, but brilliance improvised amid the tension of a real game—blurring the line between artistic invention and intuition under pressure.61...Ke2

This is the only move to avoid losing the e-pawn. Curiously, as in well-constructed endgame studies, the knight will soon capture the e-pawn and position itself to stop the promotion of the other pawn, should it still have such aspirations.

Gukesh replies immediately. After barely a second of thought, Magnus suddenly realises the inevitable: not only can he no longer win, he is lost. With the next move,

62.Rf4

the fall of the e-pawn becomes unavoidable. The sudden insight hits him.

In a fit of frustration, Magnus slams his fist against the table, knocking over most of the pieces. Then, almost as an automatic yet dignified gesture, he extends his hand to resign, stands up abruptly, and stops the clock.

Symbolically, after the chaos, it was almost as if only Gukesh’s white king remained standing—a silent witness to one of the most stinging defeats Carlsen has suffered in recent times. It was not just a personal triumph for Gukesh: it was also a clear signal of a changing era, an 18-year-old overcoming the most dominant player of the past decade.Symbolically, after the chaos, it was almost as if only Gukesh’s white king remained standing—a silent witness to one of the most stinging defeats Carlsen has suffered in recent times. It was not just a personal triumph for Gukesh: it was also a clear signal of a changing era, an 18-year-old overcoming the most dominant player of the past decade.

1. Technical Note (on 52...Ne2+)

In the history of chess, not all defeats arise from gross blunders. Some stem from poor decisions in complex positions; others from oversights so simple they astonish. It is worth recalling a singular example from the career of José Raúl Capablanca, in the Karlsbad 1929 tournament, one of the strongest events of its time. Playing Black against Friedrich Sämisch, Capablanca played:

9...Ba6??

A mistake as rare for Capablanca as it was painful. After the precise response 10.Qa4!,

Sämisch created a double threat: attacking the bishop on a6 and pinning the knight on c6. The follow-up 11.d5 sealed the idea: the knight cannot move, and White wins material without compensation. Capablanca, aware of his error, fought on and eventually resigned on move 62.

This is a true blunder in the strictest technical sense: an oversight both obvious and unforced, not brought on by the complexities of the position or by time pressure, but by a visual lapse uncharacteristic of his stature.

By contrast, in the recent game between Gukesh and Carlsen (round six of Norway Chess 2025), the move 52...Ne2+, while ultimately decisive, was by no means an obvious mistake. Rather than a hanging piece, as many commentators have eagerly claimed in search of wows, it should be understood as a decision made under extreme Zeitnot, in a richly nuanced position. The error did not stem from a tactical blind spot, as in Capa’s case, but from choosing the wrong path in the face of remarkably precise defence by the opponent. Not all defeats come from the same kind of mistake, and that distinction matters.

2. Historical Refutation

For decades, an anecdote circulated aiming to explain Capablanca’s blunder by invoking off-the-board factors. According to popular accounts (repeated by David Levy and Stewart Reuben in The Chess Scene (1974), and later by Garry Kasparov and Dmitry Plisetsky in My Great Predecessors), the “blunder of the year” was caused by the unexpected appearance of Capablanca’s wife in the tournament hall, at a moment when the Cuban champion was allegedly involved with another woman.

However, chess historian Edward Winter examined the origins of these versions in detail and demonstrated that:

The only documented explanation Capablanca gave was recorded by Albert Becker in the tournament book. There, the Cuban stated that at the moment he played 9...Ba6, he mistakenly believed he had already castled, and thus thought he could safely continue with 10...Na5 after 10.Qa4.

Edward Winter [2] traced the earliest literary origin of the legend to an article by master Esteban Canal, published in 1958. Even among the various versions attributed to Canal, key details vary significantly from one account to another. In Winter’s own words:

“Taken jointly, the narratives by Canal, Kmoch and Flohr suggest that something involving one or more women occurred in the context of Capablanca’s loss to Sämisch. The unresolved questions are what, who, where and when.”

3. Anand's View

During the tournament, Viswanathan Anand gave statements to the Press Trust of India (PTI), analysing both the outcome of the game and Magnus Carlsen’s emotional response. According to the former world champion, the Norwegian felt that his authority was being challenged by a much younger opponent, which fuelled his particular desire to win that game.

“He wanted to draw some line in the sand”, said Anand [3], referring to Carlsen’s urge to reaffirm his position against the new generation. The loss, especially from a promising position, was a harsh blow. In Anand’s words, this might explain the frustrated reaction: the loud bang on the table, the shout “Oh my God!”, and the immediate departure from the playing area. The scene was witnessed live by millions around the world; some stunned, others simply bewildered.

Vishy also pointed out that the FIDE might soon address what happened, assessing both the players' behaviour and the impact such emotionally charged moments may have on the public’s perception of chess.

4. Beyond Victory

I hope the reader won’t draw a simplistic conclusion; that the outcome is all that matters, or that only the result counts. That would betray not only the spirit of this article, but also what I strive to teach every day in the classroom. If there’s one profound lesson that chess, like life, offers us, it’s that the journey matters just as much as the destination.

Losing a well-played game can teach more than a lucky win. Sometimes we win and learn. Sometimes we lose and still learn. The key is to never stop learning.

Celebrating a fair and well-earned victory, such as Gukesh’s, is not about denying the merit of the opponent or glorifying the other’s defeat as humiliating. Rather, it is about recognising that there are moments when the board rewards those who persevere, those who calculate with clarity under the utmost pressure. If I seem to stress the ending a little too much, it is because I believe that those final moments, played under time pressure and with nerves on edge, reveal as much about character as about strategy. Not because winning is all that matters. But because when one wins like that, one learns as well.

5. References:

[0] The title we chose for this article is taken straight from Magnus Carlsen’s official X account (formerly Twitter). It hits hard, but from a grammatical standpoint, it bends the rules: “You best not miss” skips the auxiliary “had” (as in “You’d best not miss”), making it a non-standard expression. Then again, that’s precisely the point. The line isn’t Carlsen’s invention; it’s a quote from The Wire, made famous by the character Omar Little. In American English, especially in casual or dramatic settings, such phrasing is not unusual. And in the high-stakes world of elite chess, its blunt rhythm feels perfectly in character.

[1] Edward Winter, “A Nimzowitsch Story”, Chess Notes, 2006. [Online]. Available at: A Nimzowitsch Story. [Accessed: 10-06-2025, 16:48].[2] Edward Winter, “Chess Note 4712: Capablanca and the mystery woman/women”, Chess Notes, 2008. [Online]. Available at: Chess Note 4712. [Accessed: 08-06-2025, 19:12].

[3] Press Trust of India, “Carlsen wanted to draw some line in the sand by beating Gukesh in Norway Chess: Anand”, Press Trust of India (PTI), 5 June 2025. [Online]. Available at: Full Article. [Accessed: 08-06-2025, 19:36].

Post scriptum:

This article was written for those who know that chess is more than just a game: it is living history, passion carved into 64 squares. There are no quick formulas here, no viral threads. Only a narrative crafted like The Dark Side of the Moon on original vinyl: like an eclipse moving slowly across the desert.

Those who read slowly will find layers, contexts, historical nuance and silent emotions behind every move. Those in haste will only skim the surface. Because this is not content, it is thought, it is memory. It is proof that some stories from the chessboard deserve more than a passing click.

This article does not follow algorithmic logic. It was written with a scalpel, not a template; with intent, not automation. Because chess is best appreciated with ideologies, with eras, with rivalries that shaped centuries. If something sounds different here, it is no accident, it is choice. It was born from another place: from patience, from respect for those who still read to understand, not merely to share.

The thirteenth edition of the elite tournament Norway Chess 2025 took place from 26 May to 6 June, in Stavanger, Norway: a city where white houses stand firm against the passing of time, while modern industry breathes in sync with the rhythm of the sea. The cobbled streets do not stop time, but they face it with the dignity of ancient stone. On the shores of the Lysefjord, chess found a fitting stage for the sounds of silence, understated elegance… and the depth of true chess mastery.

A Stage Worthy of the Game

In the open section, six world-class players competed in a double round-robin format: facing each opponent twice while alternating colours. The term “round-robin”, so common in sporting regulations, is often linked to the French expression ruban rond (“round ribbon”); an etymology lacking solid evidence and, moreover, implausible from a phonetic standpoint. By contrast, there is clear documentation from the late 17th century showing the English use of round-robin to refer to protest letters signed in a circle, in order to obscure the hierarchical order of the signatures. From there, the modern sense may have emerged: a structure in which no one is left out, and everyone faces everyone else.

The time control was demanding: 120 minutes per player, with no increment until move 40. From that point onwards, each move added 10 seconds. If the game ended in a draw, the Armageddon tiebreak came into play: a no-return decider in which White had 10 minutes, Black had 7, and both received a 1-second increment per move from move 41 onwards. The rules are simple: no draws allowed. A decision must be reached.