In the last round of the Uruguayan Chess Championship (April 2025), an interesting pattern emerged in my conversations with several players, organizers, and enthusiasts. When I mentioned my intention to relaunch my chess site and revive the History of Mathematics forum, some reactions were as sincere as they were unsettling:

People don't read like they used to.

No one has time for long texts anymore.

Social media is all I look at now.

I found these observations to be very reasonable. In a world overwhelmed by headlines, notifications and information condensed into 15-second snippets, it is not surprising that attention is diverted. However, there is one very critical element that escapes these platforms: true understanding.

Beyond the Scroll

Neither chess nor mathematics can be learned through shortcuts. They require structure, intuition, time. And that doesn't fit in a carousel or a video that disappears in 24 hours.

This site is born—or perhaps reborn—as a necessary response to that void. It doesn't aim to compete with the noise, but to offer something else: content with time. Analyses that explain in depth. Problems that spark curiosity beyond just the answer. Texts that leave more than a fleeting impression.

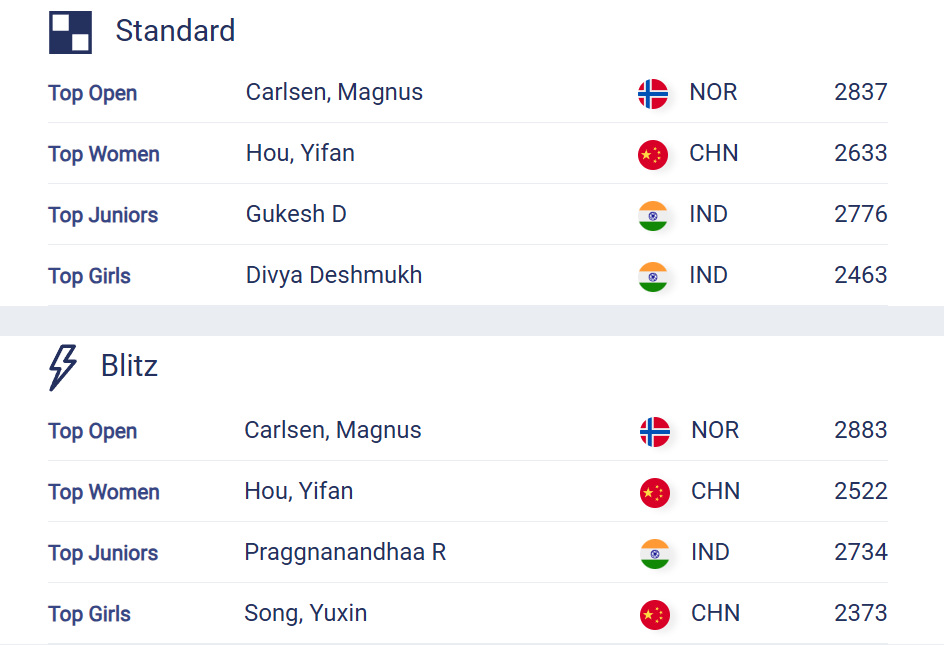

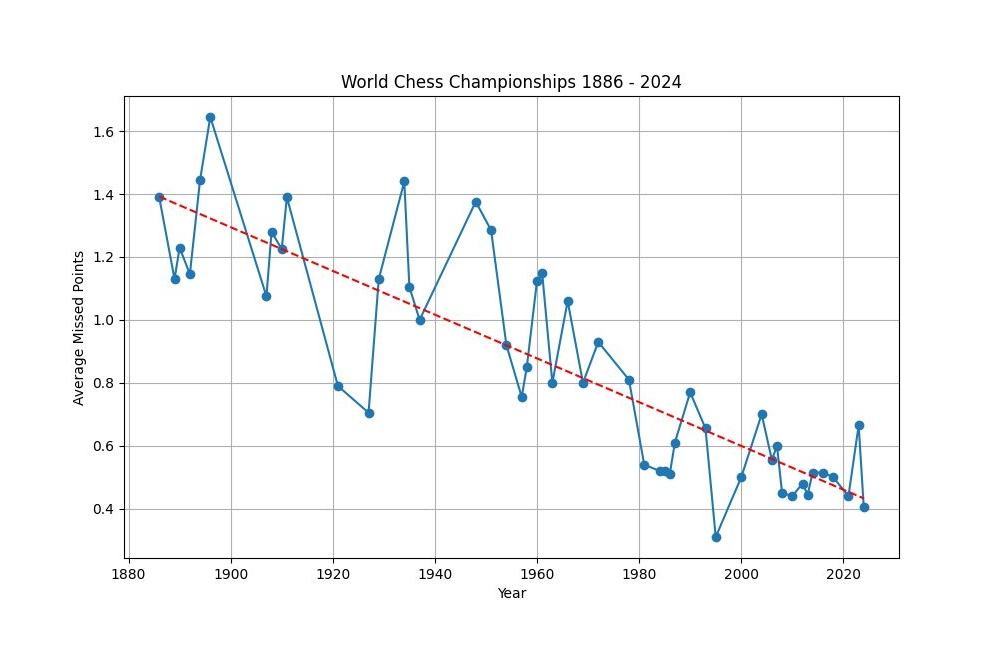

Bobby Fischer didn't learn through reels: he learned Russian to read Soviet chess magazines. Magnus Carlsen didn't become world champion by watching TikToks: he analysed thousands of classical games.

Ideas Matter

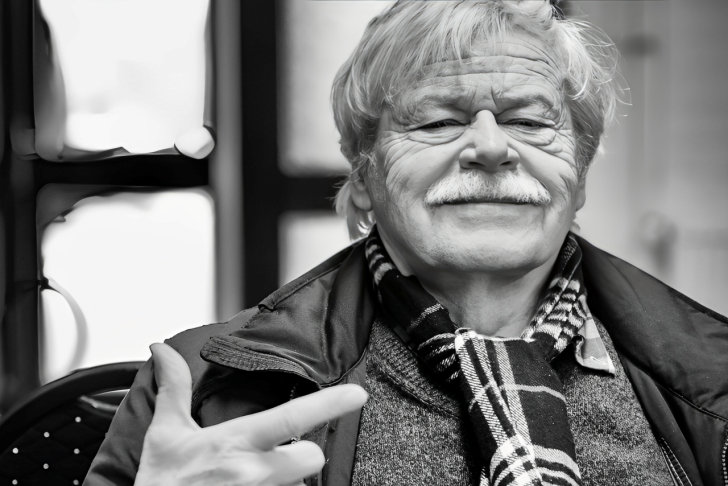

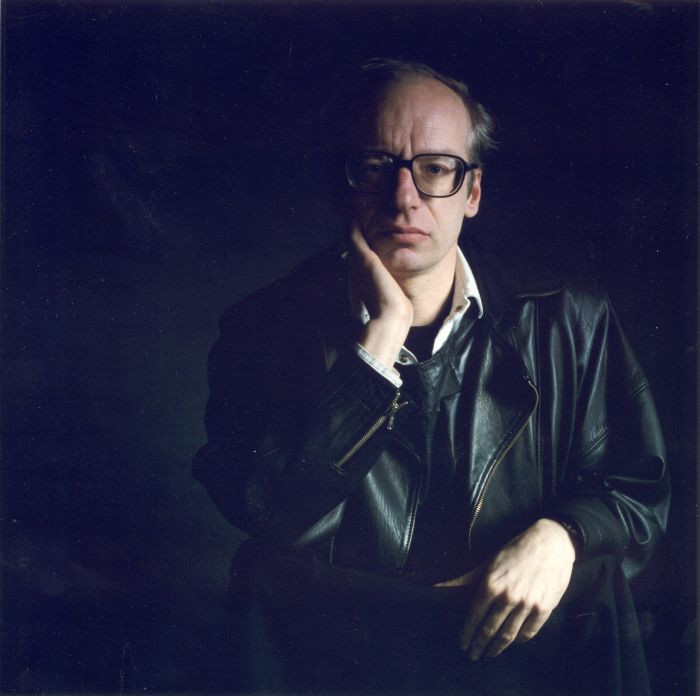

Throughout history, great minds have understood that true wisdom lies not in discussing people or transient events, but in the power of ideas. One such figure was Rudolf Kalman, electrical engineer and mathematician whose work transformed modern control theory. He once recalled an inscription he found in a Colorado Springs pub in 1962:

Small minds discuss people.

Average minds discuss events.

Great minds discuss ideas.

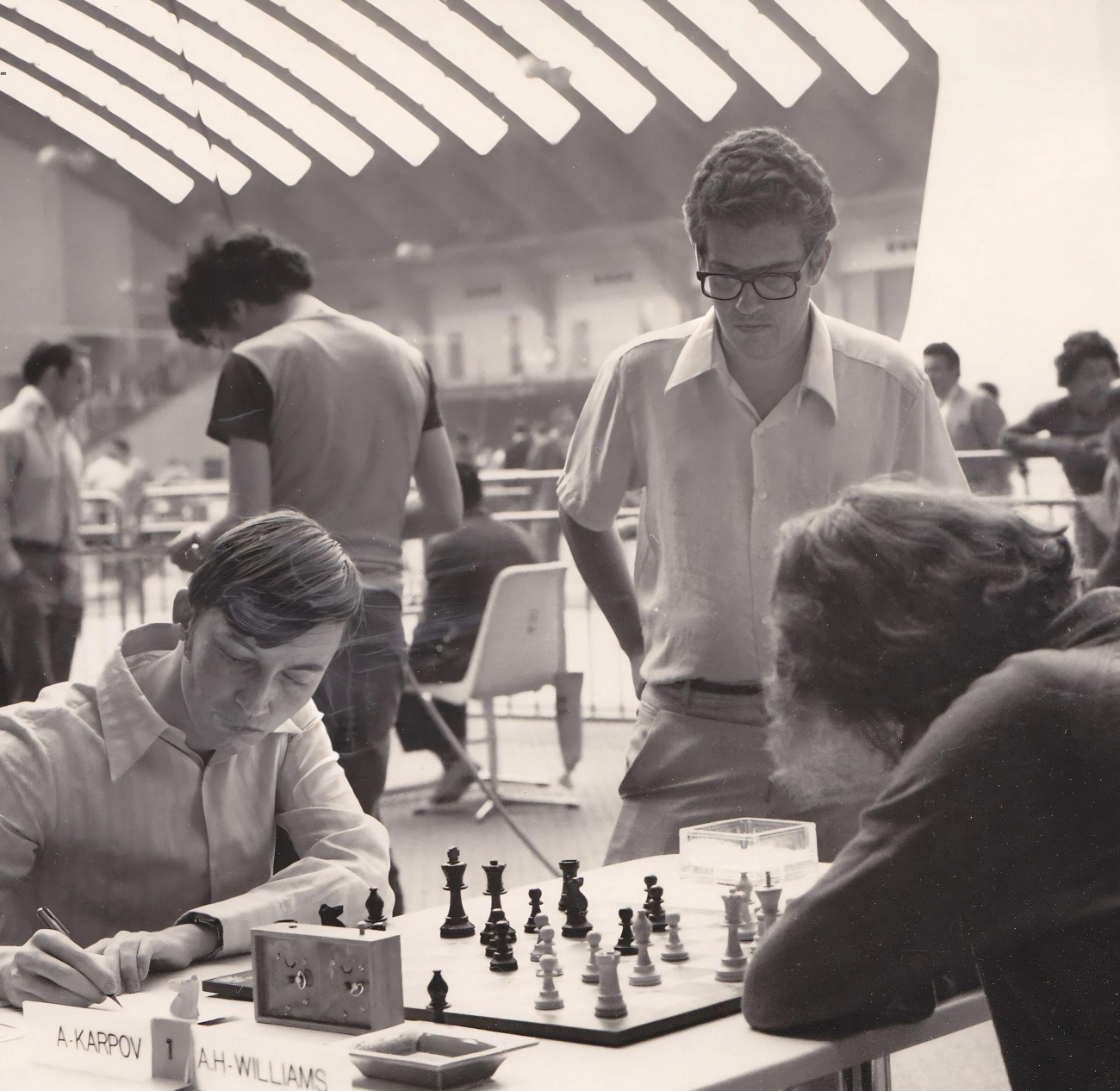

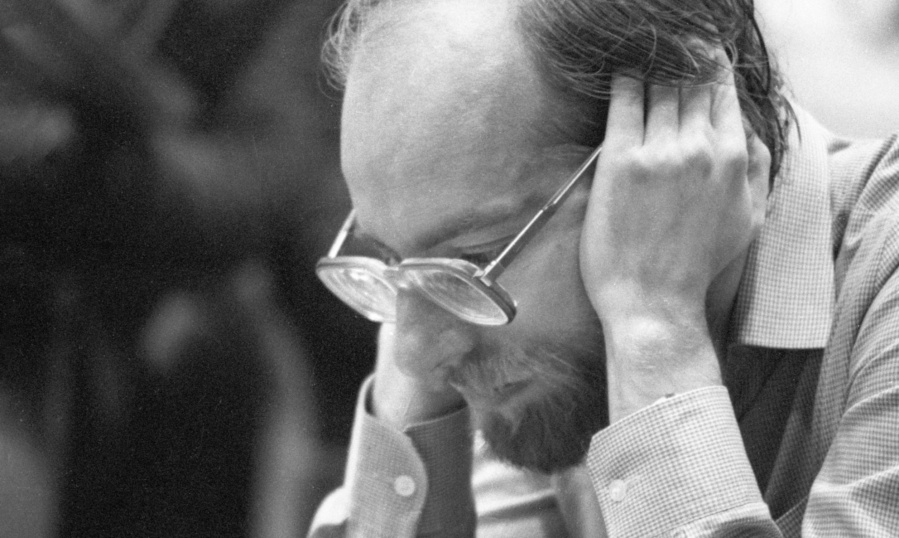

Kalman held to this way of thinking, and his actions always reflected a deep search for meaning. This same search resonated with another singular mind of the 20th century: Marcel Duchamp, passionate chess player and pioneer of modern art.

In a lecture given on August 30, 1952, during the annual meeting of the New York State Chess Association in the village of Cazenovia, Duchamp shared a memorable insight:

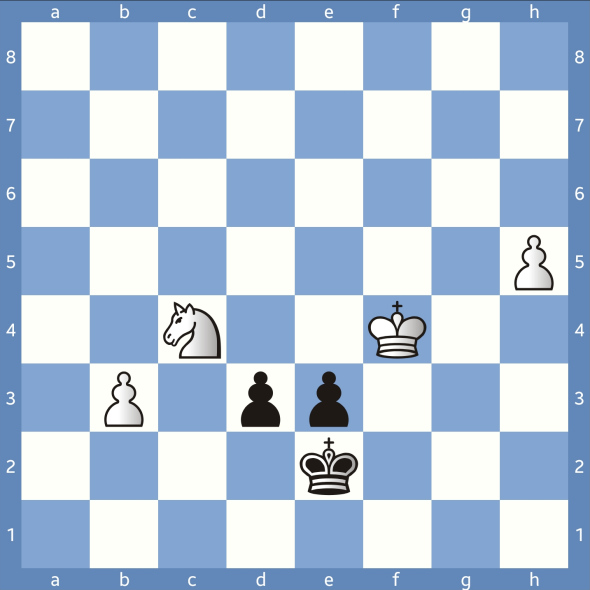

The beauty in chess is closer to the beauty in poetry; the chess pieces are the alphabet that shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, while creating a visual design on the board, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem... From my close contact with artists and chess players, I have come to the personal conclusion that while not all artists are chess players, all chess players are artists.

For Duchamp, chess was much more than a game: it was a way of thinking, creating, marvelling at the mind in motion. For him, the board was a canvas, and the pieces, an alphabet that shaped abstract thoughts. He opposed reducing chess to mere moves or results, elevating it as a philosophy of exploration. Each move, in his view, was an opportunity to discover beauty and meaning. Chess was a gateway to a world where the human mind ventured beyond the conventional, creating ephemeral masterpieces that challenged the boundaries of logic and art.

A Door Reopened

In this space, we continue that same search for understanding. To understand thoroughly, to take a moment to contemplate, to link concepts across disciplines—that’s the entryway we aim to keep accessible.

Although a significant portion of our content is freely accessible, we also offer exclusive materials for committed subscribers and premium members. Join us to explore further and discover new insights.

In the whirlwind of the instantaneous, amidst the noise and frenzy, is there still room for enduring ideas, for thinking that doesn't expire? Thinking deliberately in accelerated times may be the ultimate act of rebellion.